1. Risk Management

Violence is a summer activity. I tell myself, running like a fool in the dark, as the sun sets before the midpoint of my long run last Sunday. No one is going to be waiting to jump out from the trail and rape you when it is 30 degrees outside. Still, I pull out a Swiss Army knife and run with it in hand for the remaining 7 miles.

There are exceptions to the rule—crimes of opportunity, bad luck, and Russian military strategy.

In 2017, Runners World released a report on “running while female” following the murders of three women over a nine-day period that summer. The article detailed the results of a survey looking at the discrepancy of harassment faced by men versus women while running:

60% of the women who responded limit their running to daylight hours.

79% of women who responded reported being bothered by unsolicited attention and remarks while running.

30% of women who responded had experienced being followed while running.

54% of women who responded expressed they were sometimes/often/always concerned they would be physically assaulted or receive unwanted physical contact while running.

There is something sinister about statistics like these. I fit in all of them: I normally don’t run at night, I’ve been jeered at while running by men hanging out of cars, I have changed routes to avoid men following me, I avoid running through parts of the city where I’ve been groped walking normally and where other women have been attacked and try to stick to trails and tracks and parks with pedestrian lanes.

I made it back to my car safely after that run, my knees aching in the cold. Part of what makes the numbers troubling is that they represent a distortion of anxiety. I am not afraid of running the way these numbers and behaviors might suggest. No, part of my risk calculus is the knowledge that I am still safer around strangers, statistically than with the people I am closest to. Runner’s World acknowledges this fact and points to other riskier situations people regularly engage in, but the disproportionate sense of fear and danger for women running alone at night persists.

Everyone sucks at risk management. If we have learned nothing from the pandemic it is that people do not know how to assess threat levels and respond accordingly.

Women facing harassment isn’t a newsflash. The problem is when it comes to mitigating risk the burden seems to always be on women to take defensive precautions—draw less attention to our bodies, dress more modestly, carry rape whistles, mace, or pepper spray. Protect ourselves. What would it look like for society to not accept women’s bodies being constantly and hostilely viewed as sex objects that men feel entitled to?

2. Adidas goes on the offense.

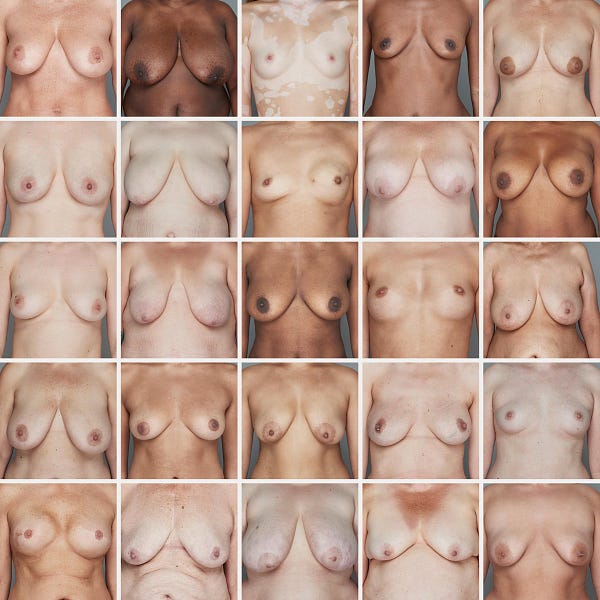

Since it’s Super Bowl Sunday, let’s talk about advertisements and wardrobe malfunctions. We’ve come a long way since Justin Timberlake and Janet Jackson’s Super Bowl XXXVIII halftime performance in 2004—or have we? This week, Adidas joined team #Freethenipple with the release of a new campaign to sell sports bras.

The question is whether Adidas is using this campaign to nakedly profiteer off women’s bodies in an exploitative manner or if they are genuinely pushing a progressive agenda to desexualize how women are perceived in our society while addressing the need for more inclusive clothing design.

The big criticism the ad received, aside from puritanical backlash, is there are no sports bras in a picture for a campaign ostensibly selling sports bras. On Instagram, they took a more demure approach prior to posting tits on main by featuring images of the indentations left on the skin from sports bras. These I personally found slightly more compelling than the clinical style catalog shot of naked chests, they also have better ad copy in the caption.

But do the products themselves back up the shock value of the ads?

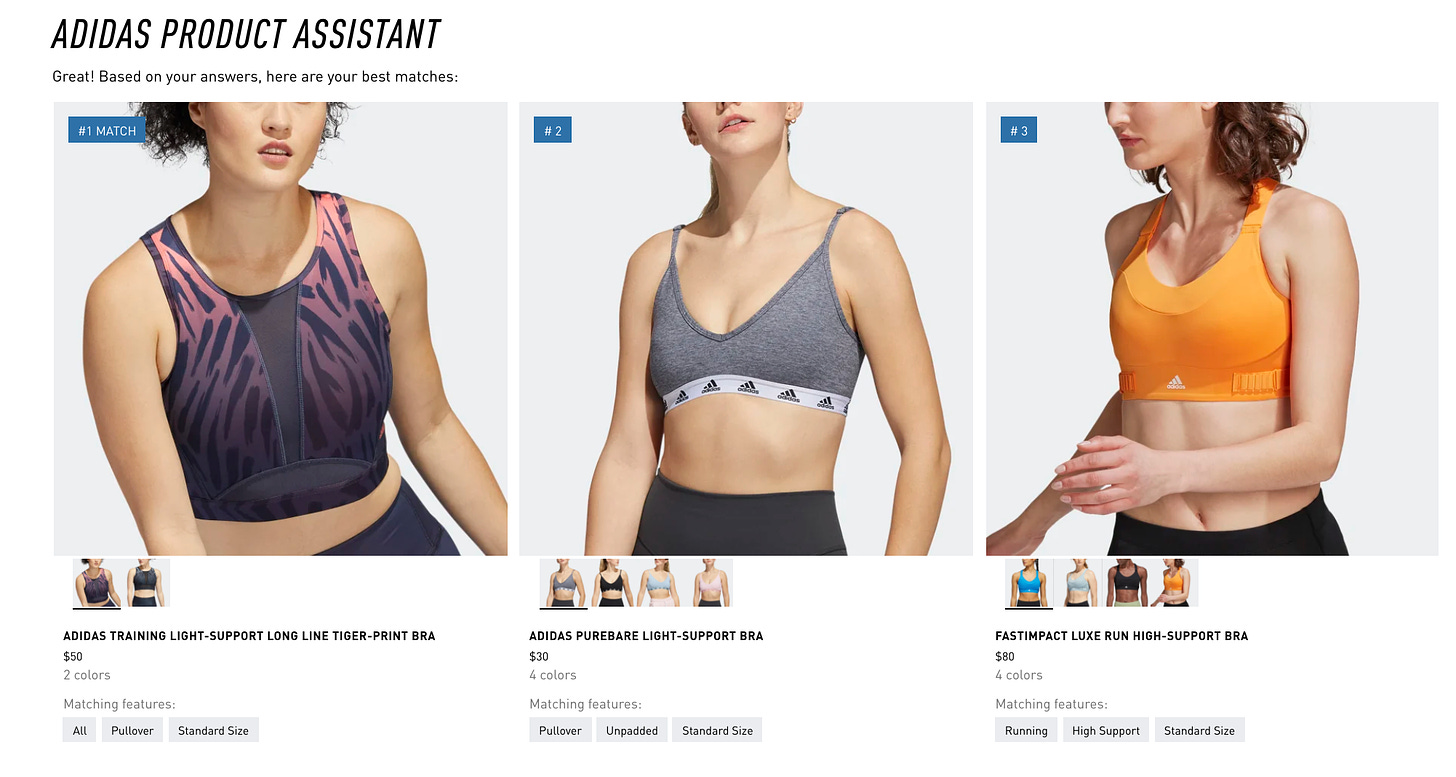

While I have not tried any of these on, they don’t look especially promising. To boast 43 new styles and have only 14 (which are actually only 5 different styles with different color options they are counting as separate designs) of them be High Support for running is disappointing. One of them has a structured cup that looks like it includes an underwire for the low price of $75. If there is in fact wire support, I highly doubt it would last more than a couple months of wear and tear before the metal poked through the fabric and started stabbing your sternum. It looks beautiful, but absolutely not. Another design has adjustable shoulder straps so you can customize the fit, another feature I do not trust under stress for a minute.

Again, I have not worn them or road-tested them, but I am skeptical. The only one that looks like it could possibly hope to rival Lululemon’s Enlite bra (which still after about 10 miles begins to chafe despite being the best high-impact option on the market) is the FastImpact Luxe design, except for the removable padding (an ironic bit of fabric to include in this case given the main purpose of padding, typically, is to keep nipples from showing).

Not only that, their Bra Finder search function is terrible. I put my main activity was running and that I was looking for high support and the #1 and #2 recommendations it suggested were light support because I also specified I didn’t want padding which seems to have outweighed the more important aspects of functionality I was looking for.

Given Adidas’s past marketing success with partnerships like Parley for the Ocean and the Ivy Park collection with Beyoncé, this campaign is in line with the brand’s forward-looking and progressive identity. But there is just something off about it, a disconnect between the ads and the products themselves. Strong messaging, but the bras don’t quite come across as a cohesive line being released, this might be attributed to the color schemes seeming random.

I really want to defend this campaign. I want to believe it is possible to change the way our culture and society views women’s bodies—but it’s probably not going to be thanks to a corporation trying to get you to buy something. The longer I sat with the ads and went through the bras on offer the more it seemed like the aggressive use of nudity was a Hail Mary to bring attention to a release of ok designs that otherwise wouldn’t have generated a huge response in a competitive market.

Will the gambit of using nudity work to achieve either goal of desexualizing women’s nipples or selling more bras? Are they actually rising to the challenge of meeting the needs and demands of women looking for better activewear when the selection they’re marketing is thinner and less impressive than they’re letting on?

The paradox of modesty culture is that it contributes to the hypersexualization of women’s bodies as sex objects. “The whole idea of modesty as protection misplaces culpability for women’s objectification, implying that a certain style of clothing can be a prerequisite for respect,” writes Sara Weissman. “Being a human being should be the prerequisite for respect.” Seeing female nipples is not the same as seeing penises, it should be the same as seeing male nipples.

The paradox of using female nudity in empowerment marketing is that their bodies are still being used as objects to sell something.

3. Links!

Adidas is also a sponsor for the Boston Marathon, which I will be running in April for #TeamBeans after the Speed Project!

“It is not acceptable that more than 50 percent of the world's population live in fear of violence solely because they are female.” An article on how harassment is not about sex, but about control.

Interesting article.

I have an entire drawer serving as outpost for disappointing bras.

Go #TeamBeans and #GoHannah!